Photo of Rosa dei Banchi by Francofranco56

Approximate reading time: 8 minutes.

I was reminded recently of the Multi-Generational aspects of climbing and my own introduction to adventure in the mountains, which was all a bit Rum Doodle, but nevertheless...

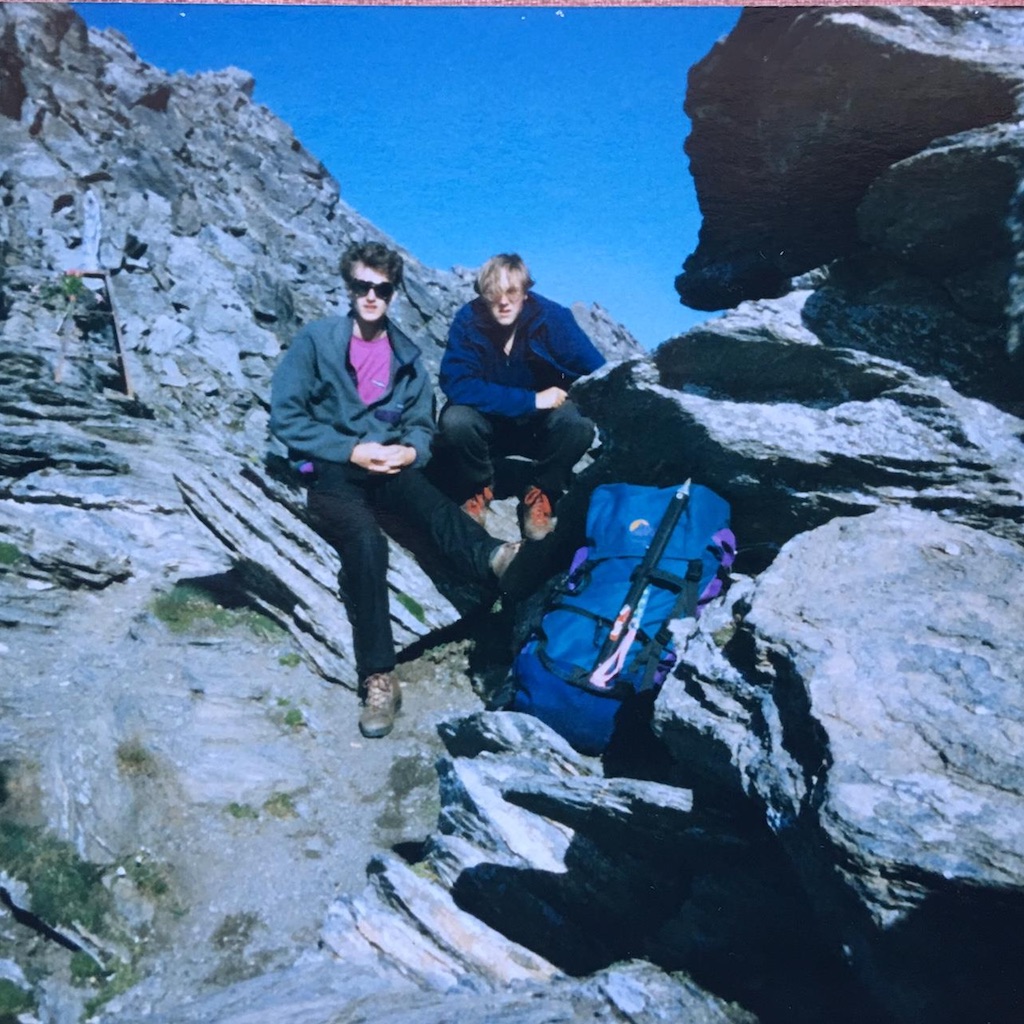

...in 1993 (my first summer holiday without parents) my best friend Paul and I headed to the Italian Alps. Along with my brother we arranged to hook up with Dino (a childhood friend of my mother’s) and his brother in law, to climb Punta Tersiva (3515m) in the Graian Alps. It suited us as an accessible 3000 metre peak that was close by Rosa dei Banchi (3164m); a mountain I had previously failed to climb under his guidance, and one which Paul and I had fixed our sites on, in this first year of independence. The previous year on Rosa dei Banchi, Dino had been unable to find the route that could take my father and his two sons to the summit. It had been my first time over 3000m, my first time trudging over a snowfield and a joyous baptism of adventure, that I shall never forget.

Dino, The Armchair Mountaineer and his brother on Rosa dei Banchi in 1992.

Dino; the man I hoped to become.

Dino is an experienced man of the Alps. He is an old man now but then he was full of life; slim, athletic with a neatly cropped goatee beard that flexed under the power of an outlandish grin. He was the man I hoped to become. His eyes smiled with an enthusiasm for the mountains that at the time was perhaps only matched by my own unrequited yearning for adventure.

As children we would occasionally visit him and his wife in Biella with our parents during family holidays to Italy. He would talk casually of weekends spent skiing or climbing in his native Alps, happy no doubt for such an easily impressed audience as my brother and I. We would wriggle with excitement at his tales. He spoke of a world I could only read about and dream about, of experiences that seemed unattainable to my limited mind.

My parents had no interest in what they perceived as the dangerous side of mountains so time with Dino was precious and added to the mystical allure of the Alps.

Fast forward to 1993 and we found ourselves squashed in the back of Dino’s Mercedes as it revved nervously over the stony dirt track that winds its way up the higher reaches of the Champorcher Valley, bulging rucksacks wedged in the boot and across our laps. We parked up a little short of Rifugio Dondena (2189 m). After shouldering our oversize packs we started the plod up towards the lake and then onto the Fenêtre de Champorcher, a 2800 metre col at the head of the valley. We paced diligently behind, as our guide - walking poles in hand - seemed to effortlessly eat up the terrain in front of him.

The wind at the col rapidly cooled us after a 700 metre ascent and, after adding a layer, we descended to Lago Ponton to camp before the next morning's climb up to the summit of Punta Tersiva. As Dino unveiled some kind of single skin, bright red Gore-Tex-Messner-Turbo-Himalayan-Legend tent we pitched our bargain-bin shelter nearby and felt a misplaced embarrassment at how unqualified we were to share this patch of wilderness.

That evening we all shared our provisions before Dino opened a small bottle of Sliva (plum brandy from the Balkans). To make matters worse, or perhaps to heighten its intoxicating effects, our guide handed each of us a Toscano to smoke. These thin dark cigars, knobbly like a wizard’s staff, were strong enough to smoke a ham, but we chugged on them manfully, feeling more grown up than ever before and frequently wincing to avoid the tell-tale cough of an amateur.

We sat around passing the bottle and chatting about mountains. Layered up against the evening cold and talking boisterously about the kind of adventures I had yet to really experience I knew I was truly where I wanted to be. I felt a sense of belonging and camaraderie which I had rarely felt outside a few fleeting successes on the sports field. I drilled down into my memory, searching through the fragments of articles I had read in climbing and outdoor magazines, trying to casually throw in names of mountains, routes or the names of gear manufacturers in the hope of displaying my knowledge of the great outdoors. In this way I hoped to gain Dino's respect and what I saw as acceptance in the rarified world of mountain adventure.

Lago Ponton

Paul and I told of our plans to climb Rosa dei Banchi in a couple of days and we reminisced with Dino about our trip the previous year. We laughed at how my brother, ever ready for a fruitless challenge, had launched himself into the icy waters of a small lake at the foot of the now defunct Ghiaccaio dei Banchi (Glacier dei Banchi). I went to bed with thoughts of climbing two mountains over 3000 metres in the next 2 days. The anticipation of which prevented me from dropping off with any haste.

“If a chamois can get there...”

A faultless sky. After breakfast we leave our camp and follow Dino, who strides off again confidently, map in hand, towards the Col di Pontonnet. I pay little attention to the path we take but instead enjoy the honest toil of walking and the unending majesty of the surrounding ridges cut clean against the blue sky. We double back a few of times and start up a tatty fixed rope. Occasionally we stop. Again we double back, hesitate. But I never doubt. Until that is, by mid-morning, the summit of Punta Tersiva hasn’t got any closer. The realisation that once again we will fail to climb a peak with Dino comes all at once when, pointing to some nimble chamois perched in a dark crease, high up on an almost perpendicular face of grey rock, our leader lets out a nervous laugh and speaks the legendary words:

"If they can get there, then surely we can to".

Maybe he could, but at this point the rest of the group speaks with one voice in saying that perhaps it just wasn’t to be. A summit eludes me.

Wandering back to the tents a little disappointed at how lamely the excursion has ended Paul and I resolve that we would make up for it the next day on Rosa dei Banchi but now we have a new problem to contend with. We have a serious lack of food and we face the prospect of one more night and then a very long day with a few biscuits and one packet of dried duck a l’orange with rice to fuel us. Reluctant to spend money at the refuge and uncertain if they were serving food we resolve to beg.

At Lago Miserin, in the sweltering midday sun, we say our farewells to Dino, Paolo and my brother (who is returning back to work) but not before coming clean about our amateurish mis-management of the food department.

Dino, momentarily dropping his cheery aura, admonishes us for our oversight and hands over what is left of the cured ham he brought with him. Chastened, we wander across the closely cropped pasture to the Refuge to see what’s available. To compound our misery on emptying our pockets we find barely enough money to get back to my grandmother’s house.

Within the cool stone walls of the Rifugio Miserin nothing is going free. After some ham-fisted haggling we do walk away with a brown paper bag containing half a loaf of bread, in exchange for the best part of 1000 Lire (probably about 3 pounds sterling at the time). But it’s all good right? We have the Rosa de Banchi in our sites as we stroll around the east side of the lake to rest up close to where the path towards the Colle della Rosa starts.

A late lunch at the lake involves chewing the butt end of the ham and hacking hopelessly with a Swiss Army knife on the rock-hard bread. It is of course inedible. But, as my mother always told me “non tutti i mali vengono per nuocere” (literally not every evil is evil) and we amuse ourselves using it to drive tent pegs into the stony soil.

We snooze, read and talk idly about our plans and what we might climb together, about the kind of gear we aspire to own and where in the world we might take it. We talk naively about running our own outdoor clothing company and how we find inspiration for colour combinations in the alpine flowers growing around us. Warm and content; sheltered from the chilly breeze, our dark fleeces soaking up the afternoon sun we feel we can go anywhere and accomplish anything.

By the evening we are famished.

Conversation turns with enthusiasm to the prospect of sharing the rehydrated Duck a l’Orange as if it could be as good as it sounds. It isn’t. It will remain the least palatable thing I ever taste. Plasticky, bitter and resembling vomit, I imagine it still lies, un-degraded, behind the rock where we emptied out the pan some 23 years ago.

For a short time Paul and I argue about whose idea it had been to bring along such a pretentious meal, when our normal dried fare of chili-con-carne and powdered mash potato is languishing back at my grandmother’s house. Then a cup of dark tea and the tranquility of the vast black, pin-pricked sky pacifies us and we turn in for the night. I suppress the urge to wriggle around in my comfy sleeping bag like a tired but excited child at a sleepover.

The next day we set off before the sun is up, conscious of the fact that we have to get up to the summit then back down to the lake, then the 30km from Miserin to the town of Bard and then a further 11km home to Quincinetto, with precisely no money.

Following the beams of our head torches as they search for cairns we climb quickly over the rocky moonscape that leads up to the Cole della Rosa (2957m). As it steepens smooth slabs of rock, patches of snow and a corner of the Ghiacciaio dei Banchi test our footing in the early morning light. The sun rises as we come over the top of the col and we feel the first welcome warmth of the new day. It fills us with positive thoughts, but not for long.

At some point, devoid of painted markers we follow a line of compacted stones and earth back over the ridge but the path just vanishes. A light patch of rock indicates that a recent rockfall has forever altered the landscape and robbed us of the track we believe we have diligently followed. We are stuck. The rock we were on slopes down like a mini Half Dome and there is a gap in the path that simply falls away to the scree some 10 metres below. Across this gap the rest of the path is still there. A few feet lower and about a metre away from the sloped rock face lies a small ledge, which could lead us back on track.

The only way to breach this chasm is to start sliding down the curved rock and then at some point push off it, jumping through fresh air towards the opposing ledge. We both peer nervously at it and then, unannounced, Paul goes for it. Throwing his rucksack down, he sits and starts to slide down the rock, tearing his trousers as he speeds up, he somehow leaves the near side of the rock and launches himself across the abyss to the opposite side. Landing in an ugly pile he turns to look at me. It is cold on the North side of the ridge but sweat is pouring down his face. What choice do I have? I throw across the packs and copy my partner’s actions.

As the dust settles we take a few moments to compose ourselves. Paul cannot believe what he has done. I am glad he went first. It only takes a few minutes of scrambling along the path for us to realise we are in fact off course and should never have come back over the ridge. What we have just gone through was never, and will never be, a path.

We improvise a scrambled route over the ridge and soon find faint but tell-tale markings leading around the South West face of Rosa dei Banchi. A year ago my un-initiated eyes could not comprehend how a path could go up this crumbling grey-brown pyramid. Now, a few peaks later, we plod up with relative ease.

The morning sky is still pale and young, our faces dark to the camera lens. The wind on the summit tugs at our clothing as we stand next to the large iron cross and embrace.

Getting down is the hard part.

From the top, to say we raced is an understatement. Heading down we managed to follow the path correctly back to the col. From there we dived down to the lake, stopping to refill flasks, then powered on towards the valley, fuelled by hunger and a desire for completion. As I recall we had not really enjoyed our modest summit triumph and would not do so until we were back down with a cold beer in hand.

Half way down the Champorcher valley we managed to cadge a lift from someone as far as the valley floor wander over to the Strade Statale 26, underneath the Forte di Bard (an early 19th century fortress that stands imposingly on a rock where the valley narrows and now houses the Museo delle Alpi). The SS26 is busy. It is the main road (other than the motorway) that goes up and down the Aosta valley and it’s the highway home. Thumbs out and strolling we thought we were nearly done.

1 hour of empty vehicles passed us by; empty cars, empty pick up trucks, tractors with vast empty trailers bouncing around as if to celebrate their state of emptiness. A nun, with 3 spare seats passed at 15km per hour. She saw us. Oh, she saw us for sure. I hope God was watching too.

Lips cracking, shoulders aching, feet bruised and quads shredded; we began to contemplate the horror of another long walk in the dying light. And then a souped-up white Renault slowed. Hazard lights started. A cartoon Italian man emerged; long hair slicked back across his skull, gold watch, shirt open, a manicured five o’clock shadow. Riccardo delivered us from evil.

Summits come and summits go. The experience and the people stay with you.

For a look at a day ascent of Rosa Dei Banchi, the way it should be done, check out this video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aRZeKkWb1oE