Approximate Reading Time: 7 minutes

In the third in a series of interviews with mountain artists I went to London to meet Daniel Crawshaw whose mountain and landscape paintings are highly acclaimed around the world and have seen him win the People's Choice Award at the 2016 Beep Wales International Contemporary Painting Prize.

INTRODUCTION

A few feet above me, on a cramped mezzanine floor in his studio (a “small white box”, as he has described it) I hear the coarse roar of a camping stove as artist Daniel Crawshaw makes us a coffee. What else what would you expect from a man renowned for his pictures of wilderness.

I take the time to look at the walls around me covered with some of his more recent work. The pictures are of a quite extraordinary beauty that transcends the worlds of mountain painting and deserve to be considered in wider artistic terms. It is unfair to describe Daniel as a “mountain artist”.

We speak of Mark Rothko and I think it is fair to say that some of his larger works, meticulously applied to formidable square canvasses, often dividing the precision of a recognizable landscape with an ethereal blanket of mountain mist do recall Rothko's signature multiform masterpieces, albeit in a more chromatically limited form. Both share a compelling quality that draws in the viewer.

"Crawshaw's work is immediate, intimate and pervasive, like a memory"

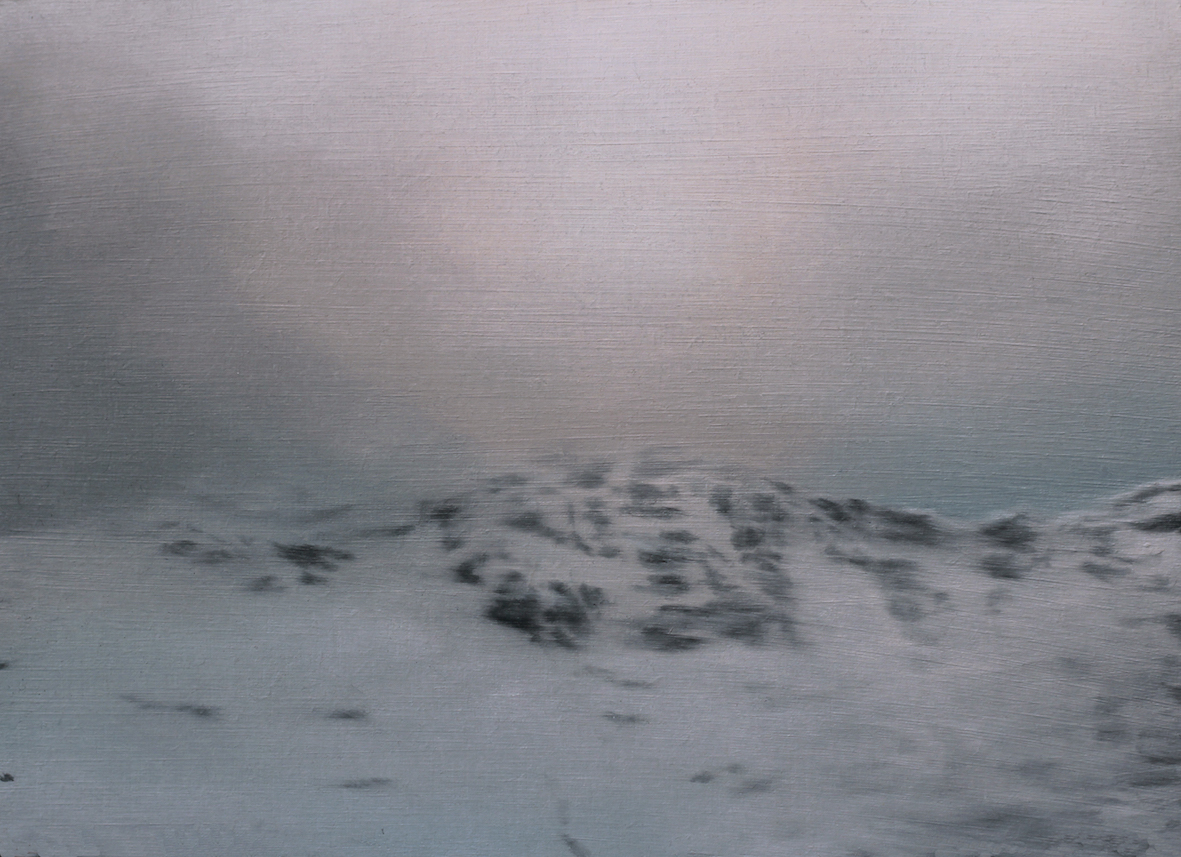

In some paintings there is stillness, in others the fleeting glimpse of a patch of snow, momentarily freed from dense clouds or a black lake, stark against the white ground. Sunlight is hinted at, the scenes at once familiar and haunting.

In Crawshaw's work, which challenges the difficulty of composition in nature by focusing on details in the landscape, I feel I am being taught to remember the beauty in each moment I have spent in the hills and mountains, not just those sun-bathed panoramas and glorious dramatic vistas.

There is a sense of honesty and reality that is not always present in landscape paintings that can easily seek to idealize the subject matter, whether through dramatic lighting or a vast scale. The connection the viewer has with Crawshaw's work is immediate, intimate and pervasive, like a memory.

Below I have transcribed the majority of Daniel’s interview, in which we discuss;

- His work in Wales & Australia

- The artist’s process & how he composes a picture

- Creating a psychological environment in a mountain painting

- Wilderness & the lack of humans in his work

- The familiarity his work stirs in the viewer

- Read more interviews with other Artists

- Where can you see Daniel Crawshaw's Work?

INTERVIEW

AM: I can hear your little camping stove working up there, boiling water for coffee, as if we were outdoors. This is something that interests me about artists who depict mountains and wilderness. To what extent do you actually get out into the mountains? Describe your relationship with the outdoors, personal and professional.

DC: I grew up in mid-Wales, so I grew up in the landscape then I studied in Leicester before moving back again to mid-Wales. Now I am in a situation where I am living in London, so the interesting dynamic is that I now have to travel to my work, to the mountains, and I come back to this studio in the city to make the work. Therefore my work is all about recall of the kind of experiences of being out in the landscape.

AM: Are these experiences that you seek out, separate to your art?

DC: They are in parallel. That’s the way my relationship has developed. My practice is I go walking in the mountains with a camera - sometimes just the camera on my phone - and gather lots of photographic material. I then come back to the studio and work from photographic prints. So essentially when I am walking I am looking for scenarios in the landscape that I can interpret into paintings. Painting and photography are meeting somewhere in my work… so I make these small, photo-sized pieces as a way of taking control of my photographic material.

AM: And do these small paintings then naturally translate into larger ones?

DC: Well sort of but in truth I make them so that I keep making work.

AM: So it’s like writing a journal, in picture form.

DC: It is. You just keep working. When I come back from the mountains I am never quite sure what is going to work so sometimes I will have prints of certain things kicking around and it will take me quite a long time to think “oh yeah, I can use that”. So I work very small and I also work very large which is another interesting dynamic because on the one hand I am referring to photography but also then reflecting in larger form the expanse of epic places.

AM: Since photography is an intrinsic part of your process, do you therefore also see the pictures you take with a camera as art?

DC: No. It’s a vehicle. What I am exploring is the difference between a photographic image and a painted image. For viewers there is a double-take because they look at something which appears to be immediately photographic but then there is the realization that it has been created by hand, over time, which fills it with more emotion, a different feeling… I mean, I often meditate on the differences because there are a lot of photographers out there now trying to make photos look like paintings. I am a painter at liberty to re-interpret what I have captured in print and in my memory.

AM: It strikes me that there is a familiarity to your pictures. For me there is a sense of reality which is not always present in landscapes - whether photographic or painted - which often tend to idealise, taking the grand, amazing moment that you might see once in a blue moon, whereas now I look around the pictures here in your studio and I think, "you know what - I actually know that much better!"

DC: Yes, that’s often people’s response to the paintings and that’s the intriguing area that I feel my work is occupying. It’s something that triggers familiarity. Often I hear people saying “ oh my God, its like that time when…” .

AM: In this way it reminds the viewer of the beauty in all moments in the outdoors rather than just that extraordinary sunset with the giant peaks, which I absolutely adore, but this is a different way of looking at the majesty of nature.

DC: Yes. If you look at my work often I am using cloud and mist to cut off the top of the space which makes for a more confined space and a psychologically charged environment. This helps to create that sense of being contained within a space. When I do have the horizon or a hilltop my concern is that it draws the mind away to contemplate what is going on behind it. I find that less interesting than the closed environment, which can be a very powerful thing. For example prison dramas work because of the confined space. If people find themselves contained it tends to create stronger emotions.

Now, a lot of the time I find that painting is about taking control… a schematic thing. Take control of the situation and you can start to guide people in terms of their experience. Of course for me, although I take many photos, in my actual painting process I am often kicking out a lot of information and taking control in that way.

AM: Well, one of the things you kick out, or at least that never appears is humans.

DC: Ye, largely. Well in some paintings there have been, in the past.

AM: I mean even the mark of the human on the landscape.

DC: I have done in the past, perhaps where there is a road in the bottom of the painting. I've got a big painting that is in Wales now; coming down one side of Snowdon it depicts the hydro-electric pipe as a compositional element. But that is an ongoing issue about whether…

AM: Is this again the pursuit of untouched wilderness? Idealizing it in as far as you depict it how you want to see it?

DC: Sort of. The thing is when you do get a man-made feature in the landscape it needs to be handled in a very conscious way because that is going to become a defining feature. I’ve made paintings of the Alps… quite a few years ago… with figures in the bottom and the painting would probably have worked equally well without them because those figures are always going to be a footnote. So I think that when man-made forms enter, they have to be a complete part. I think when there is a figure in the landscape it compromises the viewer's own presence - you are shut out.

AM: Like the Caspar David Friedrich silhouette, overlooking the landscape.

DC: Absolutely.

AM: Give me a little insight in terms of composition. Nature does not suffer the constraints of a frame and anyway as a human I can see beauty in just about everything so how do you decide when you have what you think is right in terms of composition?

DC: I think a lot of the time what's going on in my paintings is a telephoto view of a landscape, going in close to a detail and at the same time the detail is asking questions as to what is going on in the whole. So I might have patches of snow that obviously extend out of the painting maybe that gives a sense of the expanse, because the viewer can see that outside of this work there is a continuation.

AM: Wales is obviously crucial to your relationship with mountains and your art, does this continue in your more recent work.

DC: As I mentioned it’s where I grew up and I have continued to go up to Wales, staying in a bunkhouse, outside Capel Curig. I like staying there and being in fairly basic conditions. In 2013 I also did a residency in North Wales in partnership with Snowdonia National Park, which came about because I was offered a show in Australia and I wanted to find a way of cementing my relationship with the Welsh landscape, through a specific body of work.

I was then able to take it with me to Australia, where I also did a residency in Gippsland, SE Australia. So I then had a show that toured Australia and was a combination of those two bodies of work.

AM: How did that differ - you not having a natural connection or affinity with Australia?

DC: That was the extraordinary part of the project. I went with no knowledge of the place apart from a few clichéd images - especially relating to the colour or feel of the place. What I found, of course, was entirely different [DC shows exhibition catalogue]. What I discovered was what is sometimes known as Australian Gothic, so I explored completely unfamiliar forests. Interestingly this is something I have to work at quite a lot: finding the time to go out and be in that position of exploring and sometimes being uncomfortable.

AM: So did you just go into the wilderness and roam on your own in Gippsland?

DC: I did, yes. I had actually done a lot of research, hired a car and looked around, but I hadn't anticipated the feelings I would experience from being in these dense forests. It was uncomfortable, perhaps from an intense unfamiliarity.

Then I came back to London and went for a walk in Kent, amongst the beech and oak, a few brambles… that’s what I grew up with; a far cry from these vast eucalyptus forests, an environment that has been here for a very long time, unmarked and utterly foreign to me. This differs from the way we look at landscape, which we seldom fail to leave a mark on and indeed certain landscapes have entered our consciousness, for example the American West.

AM: From looking at the Australian pictures it looks again like the pursuit of real wilderness.

DC: Yes it is. So, the show was called High Country Gothic and in the introductory essay there is quite a lot written about the Australian Gothic which is almost like a character in its own right, having a certain draw on people. If you think of Picnic at Hanging rock - in the end it’s about the power of the landscape.

AM: Your work seems intensely personal to me, how do you see it.

DC: That’s the beauty of going back somewhere, like Wales. You see it in different conditions and those throw up different scenarios. There’s one here which is on the miner’s track towards Snowdon. A lot of people will recognise something familiar in these lakes and profiles of mountains. With Snowdonia, for a painter, there are certain elements in constant flux: cloud, water, lakes - endless variations. Sometimes I feel like Giorgio Morandi, the mountain's elements are my vases and I am endlessly rearranging them.

AM: But also in Australia...

DC: Yes, it was an achievement for me to go to Australia and actually find a personal connection with that landscape and when I showed that body of work in Australia it was very interesting to see locals thinking; "he has responded in a way that we associate with as well". I have sold four of the largest paintings I did to the Gippsland Art Gallery for their permanent collection. I think given that I only went for five weeks it was a remarkable achievement to go somewhere utterly foreign and find something personal.

AM: With Wales being so prominent in your make-up, is there any desire or a need to explore other places?

DC: Absolutely. I am champing at the bit all the time. I've been busy with these shows in Wales but I have long had the idea to go to the Andes and Patagonia, where there is of course a large Welsh community. My father lives in Canada and I have painted there. I made a body of work that was based on my experiences in the Rockies, around Lake Louise. I came back with a collection of images of frozen wilderness, pine trees, snow and that made for something again quite gothic, like parts of a horror story. I was actually doing some research in the Stanley Kubrick archives, looking at The Shining and was studying the role landscape plays in that movie. Kubrick sent a photographer out before hand… but the odd thing is if you watch The Shining, there is very little in terms of shots of the landscape. And this comes back to the creation of a psychological environment, something I try to do in my paintings.

AM: Daniel, thank you of your time. One final question, which mountain artist would you like to see interviewed next on The Armchair Mountaineer?

DC: I have to say I struggle with the definition ‘mountain artist’ and hesitate to categorize artists through their subject matter. There are so many creators who work with themes that might, at times, refer to mountains or define mountains as a significant part of a rich and varied practice. Emma Stibbon is one such artist.

CURRENT & UPCOMING EXHIBITIONS

- Martin Tinney Gallery: Daniel Crawshaw has a number of works in the Martin Tinney Gallery: 18 St Andrew's Crescent, Cardiff, CF10 3DD www.artwales.com

- Maverick Projects: Daniel has a show opening in Peckham on the 26th of November.

- BEEP: Wales International Contemporary Painting Prize. See Daniel's work from the 16th November at the Arcade, Cardiff.

- You can also visit the artist's studio in Bussey Alley, 133 Copeland R, SE15 3SN, near Peckham Rye station.