My Wilderness Appreciation; Hunt, Hunting and a Dog

Approximate Reading Time: 8 minutes.

WHERE DOES MY FASCINATION WITH MOUNTAINS AND WILDERNESS COME FROM? IT IS CERTAINLY SOMEWHERE BETWEEN THAT OF A CLIMBER AND A POET. THAT IS TO SAY I AM NEITHER.

Claire Elaine Engel, in her excellent History of Mountaineering in the Alps talks of Shelley’s beautiful descriptions of Mont Blanc observed during three days “under the eye” of this peak, in which he ventured onto both the Mer de Glace and Bossons glacier in the Chamonix valley. “That was not mountaineering” she comments. I feel that were Engel to have taken a peek at my climbing resumé she would have been marginally less dismissive.

I have not used a rope for a good few years now but my feeling, for want of a better word, relating to mountains and wilderness has not changed. There have been years when I have found little time to be in a wild place but when an opportunity has presented itself the spiritual uplift that I have experienced has always been as strong. At the risk of the most ghastly and gushing cliché, I really do feel that wilderness is my God. I may not go to church often but my faith is unwavering. It is indeed something that for a long time I took for granted but as I have grown older I realise that it is not necessarily a seed within all of us, that simply requires a little encouragement or education from an aficionado in order to flower.

Nature; its beauty, its majesty and its power are not, much as we wilderness lovers might like to believe, innately attractive to all of our fellow humans despite how rapidly opinions evolved over the last 300 years or so. I should point out that the appreciation of wilderness and a love of mountaineering are also not necessarily mutual, again much as we might like to think they are (many a professional sportsman is not in love with his sport). However the latter is often a vehicle for experiencing the former which, in my personal experience, means they are married. I suspect of course that each one of us has his or her own reason(s) for “worshipping" mountains and wilderness and perhaps within our own belief systems we do all cross over in some place (I look forward to seeing some Venn diagrams). But it is personal. So when was this born, in my case?

Jump to Book List

“THESE FANCIES OFTEN WOVE THEMSELVES INTO THE FABRIC OF THE NIGHT”

As I recall the birth of my appreciation of the wilderness came about through summer holidays in northern Italy. As far back as I can remember my parents, my older brother and I, drove across France to stay with my mother’s parents in Quincinetto, Italy; a small village on the edge of the Alps, on the border of Piemonte and Valle d’Aosta.

Although almost incidental to our holidays the proximity of the Alpine uplands to our ultimate destination meant that everything that represented our march towards them, and then the mountains themselves came to symbolise the unbridled joy of the summer break. The journey always took two days with a night in a modest hotel or campsite and after a day and a half of sticking to the burning faux leather seats of a 1970's Vauxhall Firenza the hazy blue outline of the Alps on the horizon meant the relief of our final destination was getting nearer. L’Autoroute Blanche - the White Motorway from Macon to Chamonix - built to whisk breathless skiers to the heart of the Alps on Friday nights after work; carried us through the hills, linking 'civilisation' and the great outdoors. Then the road signs to the Mont Blanc tunnel meant Italy was close.

Quincinetto - the "ultimate" destination.

Once we had run the gauntlet of the Tunnel du Mont Blanc, windows firmly jammed due to extravagant parental warnings of immediate intoxication and death by fumes, it was customary to stop at a service station at the entrance to Val Veny. My parents drank the first decent coffee since leaving home. My brother and I drank orangeade and stared at the air guns and Swiss Army penknives in the adjoining shop. As well as lusting after toy guns and real knives this stop afforded me the opportunity to look at a glacier.

To me the meagre end of the Brenva glacier was a tantalizing ooze of rock and ice that spoke of romantic notions from which my life was far removed and which I didn’t fully understand; danger and death. In truth ice and snow were barely visible under the mass of crumbling grey rock grinding down the mountain at an imperceptible pace. But it was a teaser of what lay higher up, an oeurs d’oeuvre for those who couldn’t eat a main course. I had heard of distant cousins or friends of friends who had “been on a glacier”. To us, little boys aged around 6 and 9, this became some kind of rite of passage, such was our naivety and ignorance of mountain climbing. My brother and I imagined that one day someone would, in the course of planning a trip, also deign to ask us to join them so we might venture into the magical realms of ice and snow. How or why this might happen we didn’t know. But we would say to each other confidently “I’m going to go on a glacier when I’m older”, our eyes glazing as we pictured our own private adventures, entirely oblivious of how Victorian a scenario we hankered after.

“These fancies often wove themselves into the fabric of the night” so recounts T. Graham Brown in Brenva, his personal history of climbing on the Brenva face of Mont Blanc. “Later on, snow mountains appeared, and a recognizable Brenva face which I climbed with delight. What moves us to such dreaming must, I think, be the wish for action otherwise thwarted, and not the wish to fulfil a thwarted ambition.”

The wish for action is all we had as children, and the rock spires and snowfields of our dreams were eminently recognizable. The brief passage on the A5 through the Valle d’Aosta was a yearly pilgrimage through the cathedrals of snow; Mont Blanc, Grand Combin, Monte Rosa. Over the years we learnt the names and they tripped off our tongues like seasoned mountaineers.

I WAS AN UNFULFILLED VICTORIAN LADY TRAVELLER.

I recall finding out that a friend of our mother’s had an ice axe and was indeed a weekend walker / climber. It was unfathomably exhilarating. I wanted to see him and talk about it. Merely the thought of possessing such a tool, or to be more precise, having reason to possess one seemed like an “official badge of Alpine travel”. This is how I might have described it aged 8 years old, in 1983. These are in actual fact the words of Miss Jemima Morrell in 1863 on Thomas Cook's original tour. I was an unfulfilled Victorian Lady Traveller.

Later, when I was perhaps around ten years old, my brother had read aloud The Ascent of Everest by John Hunt. I didn’t have the desire to read and it seemed foolish that we both read the same text. I like to think of it as an early demonstration of a talent for delegation but my father did not look at it in such positive light.

Read more here on Everest Books.

This first taste of mountaineering literature allowed us to discuss the difficulties in climbing the high mountains that we saw with the kind of blissfully ignorant earnestness only children can muster. We knew we weren’t in the presence of Himalayan highlands but the difference was negligible. The surrounding peaks deserved a pious respect because we couldn’t, and never really thought we would, get near their summits.

As was the case later with Herzog's Annapurna (although I read this one myself aged around 13) Hunt's detailed explanations of expedition equipment and preparation, that I heard and only partially understood, were like the difficult part of the gospel. It's still gospel. Everything John Hunt described I took to be the final word. I did not imagine that anything had changed in the intervening 30 years and climbing was as he described it. Perhaps it was his rather matter-of-fact manner that never over-dramatises the account. Perhaps simply the way my brother read it.

It was a remarkable story from beginning to end and in some way I envisaged myself laying siege to an Alpine 4 thousander. I knew nothing of mountaineering history then and the conquest of Everest was the greatest of adventure stories to which I could in some small way be connected, by simply looking at the hills and mountains around me. Dreaming cost nothing and didn’t require the prior approval or indeed cooperation of grown ups.

STALKING MAN-EATING TIGERS...

Even before imagining myself as a timeless hero climber I had developed some affinity for the wilderness. Having been brought up on the edge of a large wood, the outdoors was an inevitable part of my childhood playground so my imagination already had a suitable backdrop. Summers in rural, mountainous Italy lent further credibility to games of make believe. It is easy to picture yourself protecting the locals from man-eating tigers when you are hunched in the long, sun-dappled grass under the shade of a copse of silver birches, water rushing down an alpine river a few feet away.

There is some irony in the fact that some of my love of the natural world is thanks to a hunter. To be more precise a hunter-naturalist (there’s a job description that doesn’t get used much these days). Jim Corbett, author of Man-Eaters of Kumaon, brought to life the hills and jungles of India not through climbing but through his adventures as a hunter, stalking man-eating tigers and leopards.

He described the art of tracking big cats - something he preferred to do alone, on foot and often accompanied by his little dog Robin. Above all I got a sense of respect for the animals that he hunted as a means of protecting the local population from further deaths. Whether I would come away with the same feelings reading it now is probably questionable. I imagine his writings might appear grossly anachronistic to my adult mind, but such is life and indeed history. Furthermore, whether every animal he killed was indeed a man-eater is probably not really clear - or perhaps it is, but his bravery in the face of these huge beasts meant he was a hero to my brother and I.

The wilderness in which he plied his rather unique trade was also the hero. Triumph in the face of adversity was especially addictive to my young mind and when the terrain is also an adversary doubly so. We had a ready made landscape in which we could play out our own adventures; the tigers were better off imagined. But it didn’t stop us whiling away the hours crouching in the undergrowth searching for pug marks in the fine silt, by the banks of the Renanchio - a mountain torrent which rumbled by my grandparents' house.

Later in life Corbett turned into a conservationist and thanks to another classic of wilderness literature I also had an interest in survival in the wilderness.

THE CALL OF THE WILD.

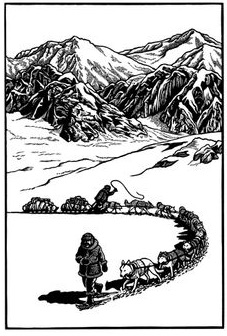

I have an inkling that I read this myself rather than availing myself of my brother's audiobooks services. Jack London’s most famous tale is the story of a dog that ultimately goes back to nature. Buck, the hero, starts the novel living in comfort in California as the pet of a Judge. Through the course of this epic tale he is stolen from the comforts of his bourgeois life and goes through a series of owners and adventures which turn him to a wild dog. The style of London’s writing is that of breathless adventure through the eyes of the animal. The dog’s journey through the hands of malevolent owners - frequently ignorant of the rules of the nature and the wilderness - is a salutary tale. All but Jack Thornton, the last of Buck’s owners, get their just deserts and when Thornton is finally killed Buck is ready to succumb to the call of the wild. Nature wins. It is brutal but it is ultimately just.

Sadly I cannot recall the conversations I had with my grandparents' alsatian, as I tried in vain to project all of Buck’s characteristics onto this rather placid and good-natured animal. Nevertheless her presence by my side helped to mould the world around me into stored up fantasies, to lose myself in the Yukon, to abandon my ways to live by the lore of the wilderness finally succumbing to the primal instinct that Jack London’s novel celebrates… at least, that is, until my mother said it was time to come in for lunch.

Without re-reading the beauty of the words is a little lost on me now, but the book has always remained in my memory thanks to a series of chunky woodcuts that came and went like milestones in Buck’s journey. I can picture them now. Trees, snow, black, white. The attraction of the wilderness; perhaps of the opportunity to find oneself, to discover something about one’s own character, was all there in the simplicity of a monochrome illustration. I was frequently unhappy at school, certainly until the age of 8 I had no friends and subject to a teacher who demonstrated a good deal of antipathy towards me. I didn’t really fit in throughout my school years - a lot of the time I was simply wearing the wrong kind of shoes. Perhaps for this reason I identified with the contentment of belonging that the wild finally delivers to Buck.

Whatever it is I am grateful to London, Corbett, Hunt and others who helped to guide me on a path of physical and mental fulfillment before my teenage years.

Book List

John Hunt

Ascent of Everest - 1953

Jim Corbett

Man-Eaters of Kumaon - 1944

Jack London

The Call of the Wild - 1903

T. Graham Brown

Brenva - 1947

Jemima Morrell

Miss Jemima's Swiss Journal - The First Conducted Tour of Switzerland - 1963

Written in 1863, for private circulation.

Maurice Herzog

Annapurna - 1955