EDWARD WHYMPER & I - TRAVELS AMONGST THE GREAT ANDES OF THE EQUATOR

Approximate Reading Time: 7 minutues.

As many of you who read this SITE will know Edward Whymper is most famous for being the first man to ascend the Matterhorn in 1865.

The successful but ill-fated expedition left 4 dead, called the very act of climbing mountains into question and shot him to international fame. Scrambles Amongst the Alps, the book he is best known for, details; “the most systematic, and, on the whole, the best planned series of assaults… made upon the high Alps”, in the words of Leslie Stephen, that most notable of alpine aficionados.

As was often the case during the 19th century many a climbing expedition was undertaken under the guise of scientific discovery.

"It will be within the knowledge of most of those who take up this book that it has long been much debated whether human life can be sustained at great altitudes above the level of the sea in such a manner as will permit of the accomplishment of useful work"

So states Whymper in the introduction to his other great work; Travels Amongst the Great Andes of the Equator. Perhaps he was still smarting from the criticism of mountain climbing per se that followed the first ascent of the Matterhorn but there is plenty to suggest that he had genuinely developed from a climber to an explorer with a wider scope to his travels.

One cannot deny that the expedition to the Andes earnestly studied the causes and effects of altitude sickness. The first edition of this book includes an appendix of scientific data and the author was awarded the Royal Geographical Society's highest honor, the 'Patron's Medal’ for his work, but I think it is fair to say that prominent in his mind and those of his colleagues, Jean-Antoine Carrel and his young cousin Louis, was the chance to climb some big South American hills. And this they did in emphatic fashion.

The book describes his expedition to Ecuador, including first and second ascents of Chimborazo in 1880 - the highest mountain in the country and at one point considered the highest mountain in the world. He also spent a night on the summit of Cotopaxi, and made first ascents of half-a-dozen other great peaks.

Jump to the list of First Ascents.

Eating the vermin which they picked out of each others hair.

In late 2001, before I knew of this book’s existence, I spent three weeks in Ecuador and visited many of the same places. So it is retrospectively that Travels Amongst the Andes earned a soft spot in my heart. It's always fun to compare one’s own travel experiences with those of days gone by, whether taking my 1889 Baedeker and driving through Switzerland or in this case judging Whymper’s descriptions of the Andes by my own experiences.

Volcan Cotopaxi (5897m) struck me as an incongruous backdrop to the half-built houses and jutting concrete pillars that made up the untidy Latacunga skyline. By contrast what struck Whymper, in this provincial town, was the sight of children on door steps, in their mother’s laps:

“To the non-observant they would have formed sweet pictures of parental affection. A glance was enough to see that all assemblage were engaged in eating the vermin which they picked out of each others hair"

How times change. Outside doorways my eyes were greeted by sandwich boards with bleached photographs and price lists offering guided trips to the summit of Cotopaxi. Every man and his dog apparently trying to cash in on the tourist industry which, along with a blooming trade in roses, exploits this fertile area of land.

Unlike Whymper my partner and I had no intention of climbing Cotopaxi but rather of ascending its neighbour Ruminahui, in order to get good views and good photos of the volcano.

In his chapter on the ascent of Cotopaxi Whymper complains of the volcanic dusts; “travelling in the interior of Ecuador during dry weather is often exceedingly unpleasant”. He was there in February. After two days and two nights of almost incessant November rain, we were in the middle of a very different experience. Like Whymper we had seen some interesting wildlife but sadly nothing of the surrounding summits.

The Juan and only.

For Whymper, with no other means of travel or transportation, the unreliability of the local mules proved a regular hamper to the party's progress. In a scene with which 19th century travellers would undoubtedly have sympathised, we struggled to even get into Cotopaxi National Park. Our first driver was turned back at the entrance for not having the necessary documents. The second attempt saw the 4x4 limping back to Latacunga with a broken suspension before the third, Juan, managed to negotiate the disintegrating tracks to get us as far as the Laguna de Limpiopungo (3880m).

Our first afternoon was spent walking around this large, quiet Andean plain, home to a variety of waterfowl and a watering hole for white-tailed deer, horses and cattle. A couple of scavenging birds, tackling the carcass of a horse on the edge of the lake, occasionally broke the stillness, and ducks scooted over the grey pane of water. Mist obscured Cotopaxi as we walked around the lower flanks of Carachaloma, wandering through the grassy paramo, camera hidden from the gentle drizzle, in a mysterious mountain world looking for a spot to pitch the tent.

After a night of downpours and a speedy morning brew we left our camp on the north western side of the lagoon and headed west up a valley into the hanging mists. The paths we followed were many, varied, and probably made by the black cattle or horses that wander the valleys and passes around Ruminahui. Visibility was minimal and it was by luck as much as judgement that we stayed roughly on course. A brief burst of sunshine brought a tempting reminder of what lay around us. The mist dispersed and the just the very summit of Cotopaxi hovered ethereally above a soft white blanket of cloud. Plants breifly sparkled as each water droplet refracted the weak sunlight but as it came, so it went and the rain was putt-putt-ing loudly on the hoods of our waterproofs by the time we reached a flat area of marshland beneath the south and central summits of the mountain. Andean gulls and lapwings circled in the sky immeditely above us.

Wilderness has a wonderful ability to appear timeless.

From this desolate, flower-rich wetland, we climbed steeply through dense tufts of thick spiky paramo grass, at times above our waists. From a distance, this grass appeared soft, with a gentle purple hue but, rising to a few feet in places, it is in fact quite coarse and on this particular day leaden with rain. Wilderness has a wonderful ability to appear timeless and, over 100 years apart, Whymper’s similar descriptions of incessant rains and tall reedy grasses, albeit in the Cayambe region, imbued my own memory of the experience with a sense of the immortality of wild places.

After a brief respite, at well over 4000m the heavens opened again. Below narrow rocky aretes claps of thunder and flashes of lightning added to our misery as we plodded up a path of crushed black volcanic rock. Somewhere between 4500 and 4600m we stopped for a rest and to ask ourselves whether time spent in the hills could be any less enjoyable. "At least there's the summit, and its pretty close" was the best rallying speech I could muster. My partner looked concerned as, guide book in hand, she sat down beside me and pointed to a passage; "the stone is heavily laced with metal, so you should descend if an electric storm threatens". Everything was conspiring against us.

Perhaps Edward Whymper and the Carrels were made of sterner stuff because we were only too happy to call it a day and turn back having failed to reach the top of Ruminahui. I remember getting lost on the way down and ploughing through the most sodden terrain imaginable. By this stage we didn’t care about keeping dry. There was nothing to keep dry. “The whole country was a dismal swamp” as Whymper would later describe some of his Ecuadorian escapades, in a rare lapse into melodrama.

Back in the tent time wasted away. Afternoon ran into evening ran into night. Oh what I would have done to have a copy of this beautiful book to while away the hours inside the those claustrophobic nylon walls?! Even for a seasoned adventurer a voyage to South America in 1879 was the journey of a lifetime - a much greater undertaking than his regular trips to the Alps - and this inspired him to embellish his work with 20 full page plates, 118 illustrations and 4 maps. Incidentally the maps he had to go by were seldom adequate and his cartographic contribution on this trip is not to be sniffed at.

Nature needs no composition.

Our second night of rain had also been punctuated by the calls of some very vociferous frogs, distant descendants from the collection of amphibians and reptiles that Whymper brought home for the British Museum. He had the generosity of describing their sounds as "music", but I can only speculate that his charitable words were due to a good set of ear plugs or a lack of empathy with the arts! Perhaps the latter for he once described the reading of novels as a waste of time... but I digress.

I really felt I would leave this Andean kingdom having never properly seen or recorded what we came to see. A real shame because if one were to invent a volcano it would look like Cotopaxi; active but relatively benevolent, rising from the lower planes in a perfect cone - a massive Mount Fuji.

But just as all hope had nearly evaporated so the clouds and mist began to give in to the equatorial sun and we became transfixed by the unfolding spectacle. In front of us Cotopaxi gradually came into view. A grey veil was lifted, revealing the ever-steepening blue-white cone of the volcano, to the west sliding into paramo and forest, to the east flattening out into a brown and grey expanse of old lava flows. On one side, reflected in the dead waters of Limpiopungo, Sincholagua (Jean-Antoine Carrel’s prize for suffering the scientific, drawn-out nature of the expedition) appeared, its steep summit laced with fresh snow. Behind us the three peaks of Ruminahui, dusted white, emerged from the thick grey sky and shone brightly in the sunlight. Fortunes and moods were reversed. Nature needs no composition, everything is in the right place and the eye can roam forever without finding fault. It was absolute and uplifting.

In the words of Edward Whymper; “Cotopaxi is a perfect volcano”.

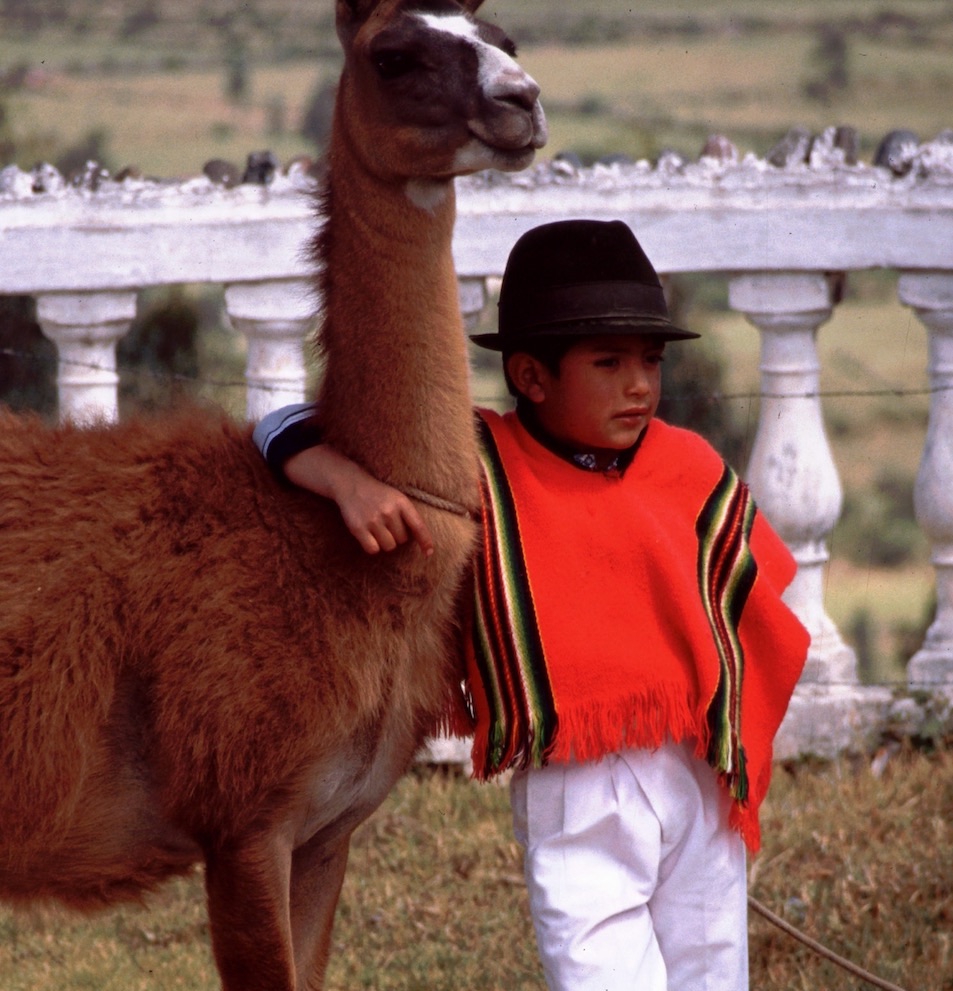

He explored much of Ecuador in a time when mountaineering, for the sake of it, was utterly foreign to the continent. The President, General Ignacio Veintemilla, did show some interest in the climbers’ exploits; “which is more than any Ecuadorian has exhibited hitherto”, noted Whymper.

This apathy towards mountaineering, on the part of 19th century Ecuadorians, enabled Whymper's team to make a number of first ascents alongside the valuable studies on the effects of altitude. The pages of Travels Amongst the Great Andes of the Equator carry an account of each ascent, but as a Victorian travel book it goes beyond the limits of detailing the climbs, delving also into Ecuadorian life and as such it is fascinating. As an early record of climbing in South America, in the words of Jill Neate - bibliographer of all things mountaineering - it is “the first of the few great classics… essential reading for anyone visiting Ecuador”. I would add to this that it is entertaining reading for anyone who is not visiting Ecuador and, dare I say it, those who have no interest in mountaineering.

List of first ascents:

First ascent of Chimborazo (6268m)

First ascent of Sincholagua (4873m)

First ascent of Antisana (5704m)

First ascent of Cayambe (5790m)

First ascent of Cerro Saraurcu (4676m)

First ascent of Cotacachi (4944m)

First ascent of Carihuairazo (5018m)