Three months ago I was sent a copy of Kinder scout: The People's Mountain by Ed Douglas and John Beatty. Here is my misty-eyed review (finally).

The first place I ever camped wild was Kinder Scout. If you don’t count a collapsed and water-logged ridge tent at the end of the garden.

I was 17, my parents were away and my friend Paul came to see me. We jumped on one, two, maybe three trains in order to get to Edale and then we walked around, through Upper Booth, along the Pennine Way to Jacobs Ladder and then rather aimlessly around the plateau.

From that day Kinder Scout came to have a special meaning to me. I spent many days in the peak district, I walked up on Edale Moor often enough in my late teens and early twenties before life dragged me away.

And, at the time, I knew nothing of its important history.

I didn’t know of Kinder as a symbol of free-thinking

This first foray into the High Peak was part liberation from the shackles of childhood and a first discovery of Britain’s wild places about which I had really only read in magazines. It opened my mind.

And yet at the time I didn’t know of Kinder as a symbol of free-thinking - the liberals of Manchester and descendents of German migrants chased off its crags and slopes by gamekeepers.

In the autumn of 1992 I had never heard of the Kinder Mass Trespass of 1932. We just rocked up and walked up. There was no one waiting to turn me away at Edale train station. We bought two tins of beans and it rained for two days. It was as English as can be.

At the time I didn’t know that Wittgenstein had complained “about the food and the incessant rain”. I loved it nonetheless. As, I believe, did he.

I haven’t been back for a few years now but it remains magical in my mind. So it was with great pleasure that a couple of months ago I was sent a review copy of Kinder Scout: The People's Mountain by Ed Douglas and John Beatty.

It’s is a book that I might not have bought, caught up as many an addictive book collector is in trying to focus on one area. But I am delighted to have received it. It is a book I ought to have bought. It is also one I ought to have read earlier, enthralling an informative as it is.

Ed Douglas's descriptions of the landscape are beautiful, clear and eloquent, transporting me back to my own early love affair with Kinder. Of course in the intervening years I had learnt of the battle for access but his exhaustive research enlightened me as to much of its, and the surrounding area’s, social, political and cultural history from before it was a National Park and a national treasure - from the German influence in the region, to the debris of a plane.

It is in fact a book which is about so much more than a place and doesn't shirk from talking about very serious contemporary issues, particularly the fragile ecology of Kinder.

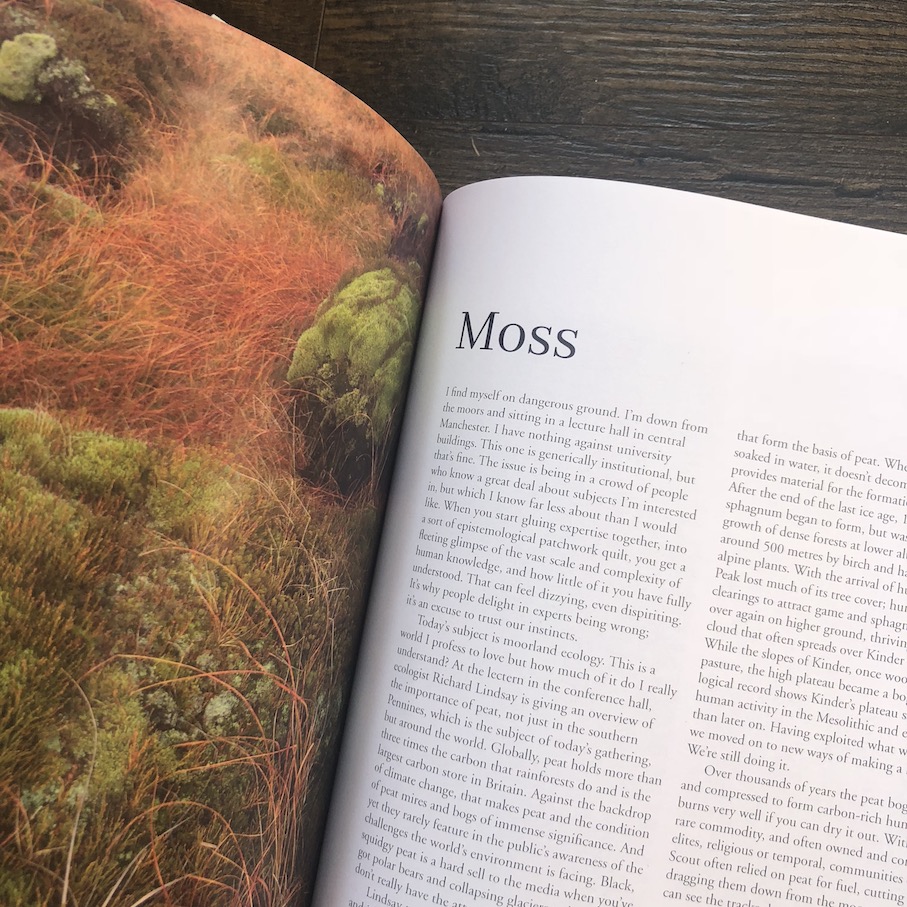

When Paul and I wandered across the sodden ground, enjoying the wind and rain on our faces, steeped in our first "solo" adventure everything was new. To say we had few cares for those couple of days is an understatement and yet, unbeknown to us, we trod on fragile ground. The chapter entitle Moss in this book had a particular effect on me as it describes "Kinder's natural world, as somewhere sunk in 'biological penury'", quoting Richard Lindsay.

In this current summer, which seems to be rivalling that of 1976 and moorland fires have again hit the headlines, it is particularly poignant. The book makes the point that peat and Sphagnum moss are not the most glamorous of ecological subjects destined to capture hearts and minds. Neither is cute. But they are key to the ecology of the area. But the battle for it's more media-friendly wildlife also appears to be a losing one, with numbers of birds of prey declining and it feels like there is little now to protect.

Land management is a complex issue, but I can't help feeling we are talking about a National Park and this book, more than my own experiences, makes me certain that in some places, where it possible land should be left to manage itself.

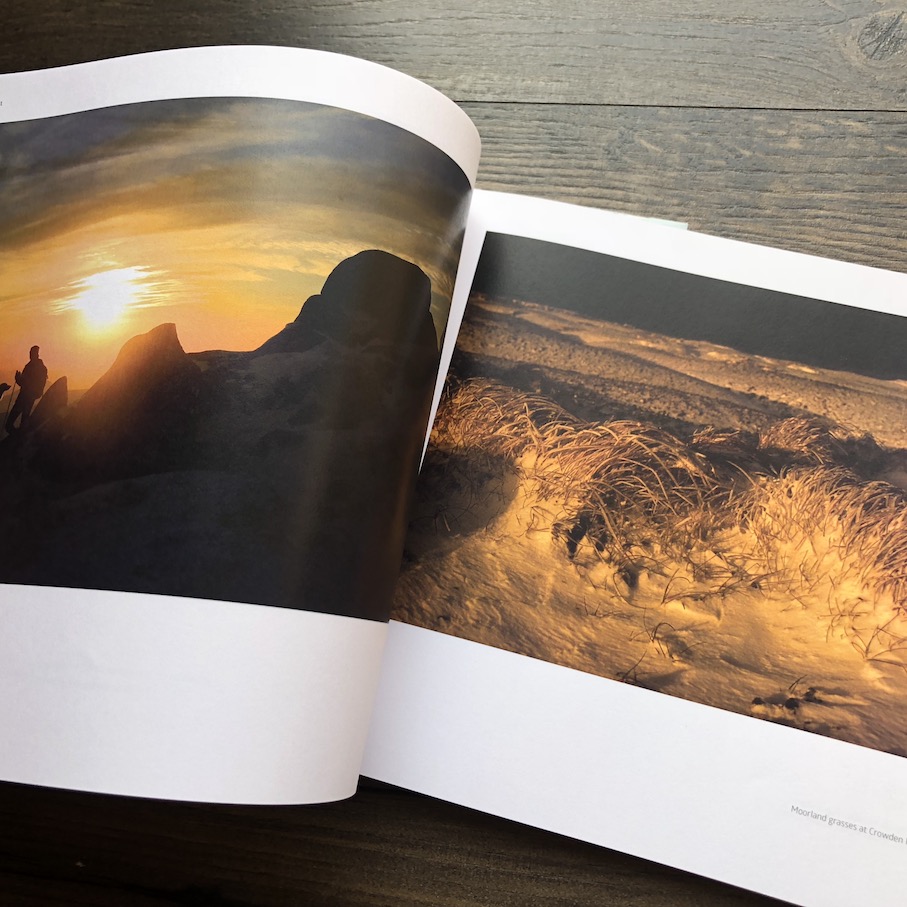

Beautiful photos

For all the endearing memories I have of the Peak District, this book also reminded how few photos I have of it. Save for a few blurry shots of wind-shaped rocks and a fearless grouse - I suppose there is something sort of poetic about that too - I have little to show for my early years enjoying the Peaks. We didn't have phones in those days.

Thanks to John Beatty’s wonderfully atmospheric photographs my imagination is enhanced with misty views of the moor, grey stones in silhouette, glorious sunsets and the important and peculiar details of daily life, which complete what is (despite its larger format) a serious book, and not something to simply rest on a coffee table.

Everyone who has enjoyed Kinder Scout and this National Park, anyone who has trodden this hallowed and historied ground should own a copy of this book. And then, when we know its history, we should all think more carefully about its future. Perhaps a cause will once again unite, not just those close by who hold it dear, but a wider body of people who treasure what such an area of natural beauty represents.

Kinder Scout: The People's Mountain is published by Vertebrate Publishing.